I was lucky enough to be invited to preview Furnishing Louisiana: Creole and Acadian Furniture, 1735-1835, the latest book from the Historic New Orleans Collection. It’s been in the works for over 30 years now, as furniture collectors (and scholars) Jack Holden and Pat Bacot, along with photographer Jim Zeitz, began documenting just about every example of furniture made in Louisiana that they ran across. Additional authors, including Cybele Gontar, Brian Costello and Francis Puig, came on board as the project progressed. Jessica Dorman and Sarah Doerries of the Collection’s publications division have been furiously editing the book for seven years.

The result is a comprehensive guide to early Louisiana furniture with over 550 pages and 1000 images. I’m not a furniture collector or scholar, but love the book for its comprehensive coverage of our history and culture as reflected in our natively-crafted decorative arts. Chapters on early cabinet makers, woods and hardware not only talk about the “nuts and bolts” of furniture making, but tell the stories of early Louisianians as their country changed from colonial French to Spanish, then to American control, influence and, finally, statehood. And it’s all beautifully illustrated with period maps and images in addition to the photographs of furniture.

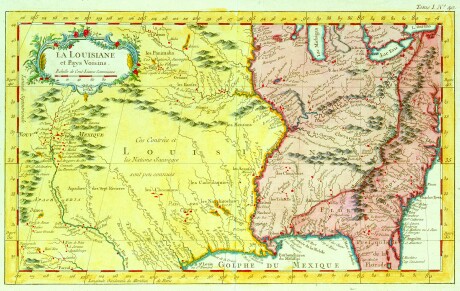

The colonial times are interesting, as we forget that Louisiana once encompassed the entirety what is now the United States west of the Appalachians.

"La Louisiane et Pays Voisins" by Jacques Nicolas Bellin, 1763; The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1975.35.

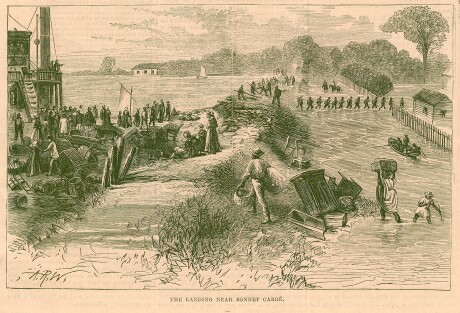

Items of early Louisiana furniture are rare finds. Fire destroyed many a plantation home along the river over the years and most of the city of New Orleans—twice—in 1788 and 1794. Another hazard, flooding, is illustrated by this engraving of a levee breach near Bonnet Carré from 1871.

"The Landing Near Bonnet Carré" by Alfred Rudolph Waud, 1871; The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Harold Schilke and Boyd Cruise, 1953.100ii. Note the armoires and tables being rescued on the right.

Some of the stories are tales of intense research and detective work. City directories of the late 18th and early 19th centuries list many names that have the occupation of menuisier or ébéniste; cabinet and furniture makers and inlay specialists; however, correlating a piece of furniture to a particular maker is often difficult as pieces were rarely signed. Vermin, mold and all the other hazards of a hot and humid climate destroyed paper labels.

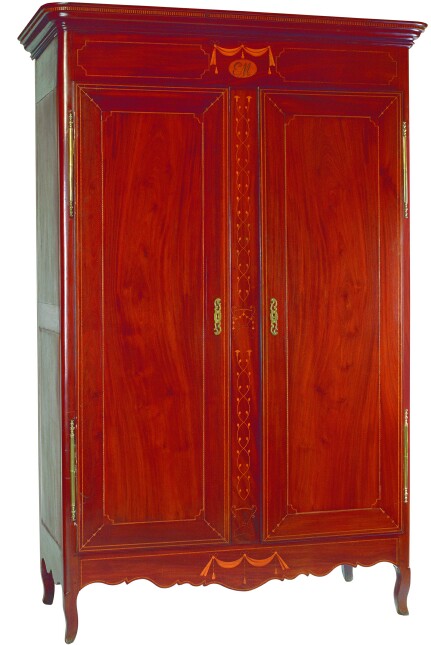

To a certain extent, the story of a craftsman dubbed “The Butterfly Man” (for a signature device he used to join side panels) and the extant furniture attributed to him, make his armoire the star of the book.

Creole-style inlaid armoire, attributed to the “Butterfly Man,” 1810–1830, from the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Robert J. Patrick, New Orleans; photo by Jim Zietz.

Coming out of the collection from the Houmas House plantation in 2003, this armoire set a record for Louisiana furniture when it sold for $140,000. The detailed account of the experts who examined the armoire’s construction and style of its inlaid decorations in an attempt to identify its maker is one of the book’s engrossing mystery stories (in a geeky, research-y kind of way; not necessarily one for Scooby and the gang).

History buffs will also be interested in the account of Creole and Creole-style furniture found in the Mississippi Upper Valley—in Missouri, Indiana and Illinois, for example—and the appendix listing furniture makers found in early city directories and newspaper advertisements.

Furniture buffs can spend countless hours perusing the catalog that makes up the bulk of the book. Photos and descriptions of every piece of furniture the authors could get their hands on are displayed in sections divided by armoires, chairs, bedsteads, buffets, tables, utilitarian pieces and the furniture of the Upper Valley.

The book is available for pre-ordering online through the Historic New Orleans Collection’s website, and I assume at the Collection’s gift shop at 533 Royal St. when it arrives (which, they say, should be sometime next week (of Dec. 13). Check the website for updated information or call the shop at 598-7147.

The Collection’s Royal St. gallery now has an exhibit of Mignon Faget’s work throughout the years. The research center at 410 Chartres St. features an exhibit of early Louisiana furniture from the Magnolia Mound plantation in Baton Rouge and an exhibit of photographs documenting life in New Orleans’ 7th Ward.

Update: I mentioned artist Rolland Golden’s work in a previous post. Fourteen of the 32 or so works he painted in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and exhibited at NOMA were acquired by the Historic New Orleans Collection and New Orleans Museum of Art.

This isn’t new news, but I thought anyone who’s interested should know they are on display at the Collection’s Williams Research Center. It’s free and open to the public, so if you’re wandering around the quarter think about popping in. There’s the furniture, the paintings and the photography to peruse. While you’re there you can take a peek into the reading room upstairs. It’s an impressive space, the former courtroom of the building’s original incarnation as a police precinct and municipal courthouse. The Williams Research Center is open Tue-Sat and the gallery and gift shop on at 533 Royal from Tue-Sun. Both are free.