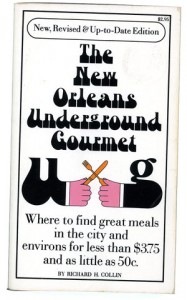

The book is a battered paperback, the “New, Revised and Up-to-Date Edition” of The New Orleans Underground Gourmet (subtitled: “Where to find great meals in the city and environs for less than $3.75 and as little as 50c.”) published in 1973 and written by Richard Collin. Collin, who died in 2010, and his wife Rima also wrote

The New Orleans Cookbook

, which remains, to me at least “the one book to rule them all” when it comes to cooking home-town favorites at home, whereever home might have been through the years.

The book is a battered paperback, the “New, Revised and Up-to-Date Edition” of The New Orleans Underground Gourmet (subtitled: “Where to find great meals in the city and environs for less than $3.75 and as little as 50c.”) published in 1973 and written by Richard Collin. Collin, who died in 2010, and his wife Rima also wrote

The New Orleans Cookbook

, which remains, to me at least “the one book to rule them all” when it comes to cooking home-town favorites at home, whereever home might have been through the years.

Unlike The New Orleans Cookbook, which is still in print, The New Orleans Underground Gourmet is a little harder to find. My copy of the book was a gift, courtesy of Nola at NOLAnotes.com. You can still find copies on the internet, depending on its condition, at a price from about $6 all the way to $237 for one that’s listed as being “new” in condition. Collin’s main gig was as a history professor at UNO, and it shows.

I had a conversation with James, The Accidental Cajun, a recent transplant and chef who’s learning everything he can, as fast as he can, about New Orleans. I told him I was working on this post, and asked if he was familiar with the book. He said he had a copy, and I asked, “Well, have you looked at it yet?” A quick look, he said, but he didn’t see any of the restaurants he was interested in learning about.

That summed up my first impression of The Underground Gourmet: it’s a perfect illustration of the city’s changed landscape, both physically and gastronomically. James first noticed all restaurants that weren’t included (because they didn’t exist when Collin wrote it); I noticed how many restaurants Collin did include that, as they say, ain’t dere no more.

The historical analytical tidbits:

In the last update of Collin’s book in 1973, he ranked approximately 154 local restaurants (plus a handful of out-of-town establishments) from 1 to 4 stars.

Approximately 21% of the local restaurants he gave rankings to are in business today. Only a couple, Brunings and La Cuisine (I greatly miss both of them), I could determine are not around today solely because of Katrina. Many had gone out of business long before the storm.

Collin awarded 4 stars to only 3 restaurants, Galatoire’s, Le Ruth’s, and Maxim’s, a Houston restaurant. Galatoire’s is the sole survivor; Le Ruth’s folded in the 80s, I believe, a victim, more than anything else, of the oil bust. Maxim’s I know nothing about other than it doesn’t seem to be around any more.

Of the 22 restaurants receiving 3 stars, 8 remain in business (36%): Acme Oyster House, Antoine’s, Brennan’s, Bon Ton Café, Commander’s Palace, Manale’s, Chris (now Ruth’s Chris) and Mosca’s.

Two-star restaurants fared worse. Of the 41 restaurants, only 8 remain, (20%) Angelo Brocato’s, Mother’s, Pancho’s (yes, that Pancho’s), Bull’s Corner (which moved to Laplace), Camellia Grill, Casamento’s, Delmonico (now an Emeril joint), and the restaurant at the Fair Grounds.

Sixteen of Collin’s 89 one-star restaurants exist today; Arnaud’s, Broussard’s, Café du Monde, Central Grocery, Felix’s, Gumbo Shop, Coffee Pot, Morning Call, Charlie’s, Parasol’s, Ye Olde College Inn, Dooky Chase, Parkway Bakery, Crescent City Steaks, Steak Knife, Bud’s Broiler and Middendorf’s.

He covered many places in the guide that earned no stars, mainly to serve as warnings to the reader to not make the mistake, as he had, of visiting them. Today, of course, we can argue over Collin’s rankings and whether they remain accurate until the proverbial crabs return to their traps, or something like that.

The Platonic Dish

Collin brought us the concept of the “platonic dish,” which, he says,

“…is my own personal accolade. The term is derived from Plato’s Republic. It simply means the best imaginable realization of a particular dish. “Perfect” would be a good translation.”

Examples of platonic dishes abound in his 1973 Underground Gourmet. From Antoine’s (oysters Rockefeller, tournedous marchand du vin, chicken Rochambeau) to the (ain’t dere no more) Zum Zum Room (honey smoked barbecued ribs).

In between those two alphabetical bookends, dishes Collin labeled “platonic” one can enjoy today include Dooky Chase’s Creole gumbo, Galatoire’s trout meuniere amandine and shrimp remoulade, Mosca’s Italian baked oysters and spaghetti Bordelaise, and Bon Ton’s Crabmeat Imperial.

Reviews and Criticism

The teacher in Collin comes out at every opportunity. His restaurant reviews are opportunities to educate readers, there was something about each establishment he though was important for them to know.

The ins-and-outs of Antoine’s labyrinthine dining facilities (and menu, for that matter) weren’t the only things Collin chose to educate his readers about in the course of his review of the old-line stalwart. It was an opportunity for him to present his philosophy of fine dining and what a customer should look for while dining in general. Discussing whether one needs to have his own waiter there, (an active issue for discussion at Galatoire’s and Antoine’s 40 years later) provided Collin the opportunity to segue into diners’ expectations:

As a newcomer you obviously are not going to get the welcome or the service a patron of twenty years who dines at Antoine’s once a week can expect. However, you will get a gracious and efficient waiter who will be willing to explain the entirely French menu and make some suggestions. You will do well to trust him. He will be making several assumptions: that you are not an expert on Creole cooking or on Antoine’s own version of it; that if left to your own devices with the huge Antoine’s menu you will inevitably make some inappropriate choices.

Now we are at the crux of the problem, not only of Antoine’s but of a great many restaurants. A few great restaurants can prepare everything on their menus well, but these are rare. A restaurant that has specialties it prepares exceedingly well is no worse a restaurant simply because it lists on its menu other dishes some of its patrons may occasionally like to order. Ordering a grilled pork chop at any New Orleans restaurant is wasteful to the point of contemptibly. Most food—and especially great food—is incomparable. Cooking is an art form. The art of dining consists in eating what a restaurant prepares best.

I think that might be the most important thought anyone can take away from Collin. As much as one might like to blame a bad dining experience on other factors, we really are responsible for educating ourselves before we spend our money. I have proven to myself many times that I have not learned this lesson yet.

What Collin didn’t address, but obviously strove to prove, is the premise that criticism can be an entertaining art form, too. Evaluating and discussing the pros and cons of the city’s eating establishments wasn’t to be a dry, “just stick to the facts, ma’am” exercise.

Famous for not holding anything back, he enjoyed embellishment, and the reader gets the idea Collin relished the opportunity to unsheathe the rapier and eviscerate, as efficiently as possible, an offending establishment. Forewarning the reader came with entertainment. Rather than make a list entitled “Downtown Places You Might Want to Avoid,” Collin instead has a chapter entitled “The Great Center City Disaster Area.”

The Poor Boy Sandwich

The poor boy sandwich (shortened in today’s vernacular to “poboy;” now an almost universally accepted spelling) was the working man’s lunch of choice and remains rightly so. The shortening of “poor boy” to “poboy” was an inevitable event, as the word “poor” would have been pronounced “po” by 99% of the working population in the city. That it became accepted as a written representation of the word, when referring to the sandwich, is not without controversy which is too insignificant to me to address further. I will use Collin’s unfailing referral to the “poor boy” sandwich hereinafter.

Poor boy sandwiches were a topic that put Collin in rapture. Rather than sum up, I’m going to reproduce his thoughts from the book entirely:

Poor boys are great sandwiches. They may resemble heroes, submarines, and grinders from other areas, but they are in a class by themselves, in the special taste of New Orleans’ own French bread and in the infinite variety of fillings.

The standard poor boy is the roast beef. The roast beef for the New Orleans poor boy most resembles pot roast. It is cut thin, placed on the hot French bread, and then slathered with a jus made from the beef gravy. A dressed poor boy then has shredded lettuce, sliced tomatoes, and mayonnaise added to it. The wetter or squashier the roast beef poor boy, the more closely it approaches that mystical perfection New Orleanians demand of this substantial sandwich.

There are other fillings that compete for first place with the roast beef. A form all its own is the oyster loaf: buttered French bread filled with fresh fried oysters. The magic that results is the mystical blend of two supernatural forces: a newly fried New Orleans oyster and freshly buttered warm French bread. The oyster loaf is the aristocrat of the poor boy family. It generally costs twice as much as the regular poor boy or comes in half the size.

Other favorite poor boys include ham and cheese, broiled ham, smoked or hot sausage, and even such unusual fillers as veal cutlets and soft shell crabs. Fried potato poor boys are just about a lost art, but they do still exist in certain heavenly outposts. And on Friday, trout and catfish poor boys can be found here and there.

One must not assume that all poor boys are alike. There are sharp differences in quality. Indeed, so bad are some of the new (and some careless old) practitioners of the art that what they serve as a poor boy is simply a loaf of French bread and some mediocre filling, merely a large and gross sandwich. The true poor boy has a magical glow best recognized by the warmth of the French bread (an unheated poor boy is an abomination), the aroma (one should be impatient to devour it), and in the case of the roast beef, an incredible moisture (it should literally leak on everything in sight).

His reviews of poor boy restaurants provide great examples of Collin’s critical style. Places that were and remain local favorites today were among the victims of his wit. Take Domilise’s for example:

Domilise’s is a popular seedy uptown poor boy stand and bar. The emphasis here is on price. Poor boys come in two sizes and cost 65 cents and 80 cents. The sandwiches are less than mediocre. The roast beef has a floury gravy, and the beef is cooked even longer than the average overcooked poor boy roast beef; the fried oysters are in no way distinctive, and the smoked sausage is unpalatable. Chacun à son gout.

That last little bit in French I thought might be some warning about a chance of getting gout from eating there but a quick look on the internet corrected my ignorance; it’s basically French for “to each his own taste.” Collin doesn’t mention the Domilise’s trout po-boy I enjoyed back in the day or the shrimp po-boy, which they are probably most famous for nowadays. People are still warned to stay away from Domilise’s roast beef.

The last remaining location of the originator of the poor boy sandwich, Martin Bros., was still in business on St. Claude in 1973, and Collin bestowed its roast beef and fried potato sandwiches with the coveted “platonic dish” rating. But, that came with a couple of warnings: the sandwiches were so small you needed to order two, and,

Martin’s is a rather seedy-looking restaurant with a large counter and a handful of tables. It is not unpleasant to eat here, but if you have any qualms, the takeout service is fast. Just be sure that you take home enough. One of the advantages of eating on the premises is the joy of being able to order that tempting second sandwich.

His favorite poor boy restaurant was Mother’s, which he gladly recommended but which locals now shun as a tourist trap. His reviews of local favorites Parasol’s and Parkway Bakery validate the solid reputations both places enjoy today and are a comforting reminder that some things haven’t really changed:

Parasol’s is a good Irish Channel bar and poor boy restaurant with excellent, freshly made versions of roast beef and ham and cheese poor boys and oyster loaves (all recommended).

…The Parkway is an old-time favorite poor boy establishment near the Fair Grounds and the New Orleans Art Museum. All of the Parkway’s sandwiches are good; the roast beef (highly recommended) is first rate, as is the ham and cheese.

Creole cuisine: An endangered species?

What, exactly, is Creole cuisine? Before the railroads came, New Orleans was basically an island; water routes were the only practical means of getting in and out of the area, at least on a commercial basis. New Orleans has a unique history of cultures that came to populate the city. French colonists from Canada France and San Dominque (now Haiti) African slaves and free persons of color (former enslaved persons and their descendants), Spanish colonists, English and Americans all came to call New Orleans home by the time Louisiana became a state in 1812.

The term “Creole” came to mean any one, of any color, born or descended from the French or Spanish, enslaved persons or free persons of color, who were born during colonial days. Creole cuisine (or Creole tomatoes, or Creole eggs or even Creole horses) was simply whatever was produced by the Creoles. Absorbed into the Creole repertoire were also many of the ingredients and techniques brought here by Italian immigrants in the late 1800s.

I’ll leave it to Professor Collin to analyze what the elements of Creole cuisine, as it evolved to the year 1973. It’s safe to say it’s pretty much the same today. I’d add that Collin’s historical explorations are really what make The Underground Gourmet a gem. I recommend getting a copy and reading everything, but a complete analysis of Creole cuisine that could not be presented more concisely except in bullet points and whether it’s wise or not, that’s what I’ve done: edited and, in some instances, paraphrased and re-arranged, Collin’s expositions on New Orleans cuisine.

Cultural influences:

- Creole cuisine is as different from classic French cooking as it is from other American cuisines. Creole cuisine has absorbed both French and Italian influences without being engulfed by them.

- French and the Italian culinary traditions have greatly enriched New Orleans cooking, but they have done so on New Orleans’ terms and with New Orleans’ ingredients.

- Local seafood resources adapted to the characteristic talents of the Italian master chef are but another example of the strength of the local Creole cuisine.

- In many ways the entire Creole cuisine is a form of soul cooking.

- African-American chefs were involved in New Orleans cuisine from its inception.

- Creole cooking tradition has long been transmitted by black chefs working in wealthy Creole homes.

Ingredients and techniques:

- A phenomenal abundance of seafood defines the genius of the Creole cuisine.

- Basic are the shellfish and the fish—oysters, shrimp, crabs, crawfish, trout, redfish, pompano, red snapper, and turtle.

- Oysters are at the heart of New Orleans grand cuisine and a staple of the workingman’s diet.

- There are two principal types of crab, a major ingredient in New Orleans cooking: the hard shell crab and soft shell.

- The hard shell crab is boiled in heavily seasoned broth and eaten with the hands or used in gumbos and salads.

- The soft shell crab is fried, sautéed, or sautéed with almonds.

- Soft shell crabs are unknown in European cooking; in New Orleans grand cuisine they are one of the most important and triumphant ingredients.

- A tour de force of local cooking is the decoration of an already elaborate dish (broiled fish, sautéed veal) with a sautéed soft shell crab.

- Lump crabmeat forms the basis for many sauced dishes and is also often used as a magnificent final touch to a restaurant specialty.

- Local trout is much more akin to striped bass in the rest of the country than it is to brook trout.

- Trout is prepared in every way, shape, and form in New Orleans.

- Trout amandine is one of the triumphs of grand New Orleans cooking. A slim margin of cooking genius separates trout amandine from fried fish with a sprinkling of nuts.

- Chicken and beef are important elements of the Creole cuisine but they are not nearly as important as seafood.

- Vegetables that are essential and central to Creole cooking include red beans, okra, artichokes; peppers; mirlitons and Creole tomatoes, a local variety with a pronounced taste.

- Tabasco and hot sauce are present on every Creole table.

- French bread, a great crusty local loaf which is the basis for the poor boy sandwich and is the accompaniment to any important meal.

- Coffee in New Orleans is dark-roasted and double-dripped and has been mixed with chicory, although it is declining, still a favorite way of making coffee.

- Café au lait is one of the distinctive New Orleans specialties.

- Delicacy is not the great hallmark of New Orleans cooking.

- New Orleans hollandaise is heavier, has more lemon (and often more cayenne), and is more often glazed than the French.

- Remoulade sauce used with shrimp and crabmeat cocktails is a hearty blend of hot Creole mustard and vinegar generally mixed with a mayonnaise base and much more vigorous than the French version.

- Every great restaurant has several elaborate baked oyster dishes.

- French chefs would no more think of baking oysters, which in France are scarce and expensive, than he would of serving crawfish without a sauce.

What’s Changed?

Fine dining in New Orleans circa 1973 meant dining in a Creole restaurant. There was no Stella!, August, Herbsaint, Bayona, Cochon, La Petit Grocery, Patois, or their equivalents, in existence. These are all great restaurants and the city is enriched by their presence, but they do offer competition for the classic Creole dining experience.

You also won’t see anywhere on any of Collin’s lists sushi joints, coffee shops, Vietnamese phở joints, Lebanese shawarma joints, Indian or Thai restaurants, brew- and/or gastro-pubs or “new American bistro” offerings. It’s the opposite of “ain’t dere no more”—they weren’t here yet.

While the city had its share of humdrum Chinese and Mexican restaurants, it didn’t get much more exotic than the old Bali Hai back in 1973. The present gastronomic landscape is a result, I theorize, (and of course I could be wrong or missing something) of local palates having been educated on a greater variety of cuisines by travel and vastly increased media exposure to cooking and restaurant shows via cable and satellite TV. Also and, I think, very influential, the proliferation of amateur and professional restaurant review and cooking how-to sites on the internet.

So the concern becomes, what will all this competition mean for the future of Creole cuisine? There’s already a backlash of sorts. While restaurateurs like Donald Link, Susan Spicer, John Besh and Paul Prudhomme take pride in presenting classic dishes and also using traditional Creole ingredients and techniques in newly created dishes, some popular restaurants have specifically spurned or minimized Creole influence on their menus. Sylvain, Ste. Marie and Capdeville come to mind, and somewhat perplexingly as the owners are aware of and celebrate New Orleans culture through their restaurants’ architecture and history to a much greater extent than through the food they produce—and by all accounts they do a good job with the dishes that they do serve.

Is Creole cuisine an endangered species? I don’t really think so, despite all the competition for diners’ attention nowadays.

I’ll leave it to Collin to present the case for its preservation. For those with modern concerns, it boils down to it being 1) regionally unique and, 2) it’s the quintessential “localvore’s” cuisine (although that word had not been invented when Collin made his case).

Creole cooking was long accessible to everyone in New Orleans, and it could be produced much more cheaply than any outside food; it was good, it was plentiful, and it could be cheap or lavish. Thus New Orleans very early became a culinary island unto itself, with a charming regionalism both provincial and sophisticated that persists to this day.

New Orleans is a city for the gourmet and always has been. From the start, with its rich European heritage, New Orleans has had great restaurants, which flourished during the days of New Orleans’ prosperity in the 1830’s, and which have given the city a tradition of fine dining unknown to any other American city. Because the cuisine is regional and because the customs and the specialties have not passed beyond New Orleans, in a sense every restaurant in the Crescent City is an underground restaurant, one that is exotic and strange.

Once the misconceptions about New Orleans cuisine are cleared up, and the necessary comparisons with French cuisine are made, understood, and accepted, one can better enjoy the undeniable glories of the grandest remaining regional cuisine in the United States.

Anyone who is wondering, or anyone who needs a refresher course on what it means TO BE New Orleans should start with Collin, at least concerning food culture. I’ve tried to present as much as I could of what I think is important in this book. I have to reiterate as strongly as possible, however, that you should get your hands on a copy and read. All of it. You will not regret it.

And remember, kids, for maximum eating benefit: “The art of dining consists in eating what a restaurant prepares best.” Now, more than ever.

Thoughts, comments, rock throwing and pitchfork-thrusting can be had in the comments below.

Love the post. I was at LSUNO (now UNO) in the late 60s-early 70s, when Dr. Collin first came to teach there. I wasn’t lucky enough to have any classes with him–he was a very popular teacher–but I had Comparative Literature with his wife, Dr. Rima Reck (herself a terrific teacher).

I still have a copy of the original Underground Gourmet book around somewhere. Collin also wrote restaurant reviews for the States-Item. He and his wife were brilliant and fascinating people, and a charming couple. What a great writer, historian, and gourmet he was. Thanks for the memories.

A friend gave me a copy of the Underground Gourmet a couple of years ago. Coworkers and I had fun reminiscing about the restaurants we ate in back in the day. It was interesting to see how the poboy filling choices have expanded so dramatically since the book was written.

And, of course, I own & love their cookbook too.